Rainis was much more than a great poet

and dramatist. As Aivars Stranga wrote

in the new history of the 20th C: "Rainis

was the major figure inseparably linked

to the birth of the independent Latvian

nation and to the struggle for freedom.

In the autumn of 1919, when newborn

Latvia faced its deadliest enemy - the

Russians and Germans under the leadership

of Bermondt-Avalov – Rainis' dramatic

ballad 'Daugava' was published as a

separate work, and the defenders of

Latvia took this pamphlet with them to

the front. In 'Daugava,' Rainis again

turned to the poetry that had provided

such inspiring power in the Revolution of

1905 – brief, emotionally charged lines:

Ejam! Uz priekšu! Uz cīņu!

Mēs negribam kalpot ne austrumam,

Mēs negribam vergot ne rietumam.

('Onward! Forward! To battle! / It is not our will to serve the East / Nor to be enslaved by the West.')"

[Daina Bleiere, Ilgvars Butulis, Inesis Feldmanis, Aivars Stranga, Antonijs Zunda, Latvijas vēsture: 20. gadsimts. Rīga: Jumava, 2005. My translation.]

Rainis was both a nationalist and an internationalist; how his socialism related to his nationalism at different points is a fascinating and complex thing. There's a study by Arturs Priedītis called "Rainis un sociālisms" in his Mans Rainis (Daugavpils: AKA, 1996). Fricis Menders observed that "it is futile to attempt to limit Rainis by the concepts of Bolshevik or Menshevik."

Menders, Cielēns and Skujenieks were the three men primarily responsible for creating the framework for independent Latvia -- drafting the Satversme we still use today -- and all three were socialists; Menders was from a poor family in Grīziņkalns (long the most Latvian neighborhood, ethnically, in Rīga), but had gone into exile after participating in the 1905 revolution. In what is considered a terrorist act, he tried to take over the Central Prison in Rīga and release the inmates; he was sent to Siberia, escaped, and acquired two doctorates (in law and economics, from Bern and Vienna). He was about to start a career as a docent in what was then the infant science of sociology, at Bern; among the rare hyper-educated Latvians of the era, he could have become the world's first professor of sociology. He was only thirty-two years old. Instead, he returned to Latvia as one of the most prominent figures in politics. (Stranga, ibid., and interviews in the press.) He was in the delegations that concluded the peace treaties with Germany and Russia, and he later led the Foreign Policy Committee of the Saeima. Menders later headed the so-called "Muscovite" wing of the Social Democrats, drafting the new party programme in 1930 – a virtual copy of the Austrian Marxist programme. In 1931, Menders' radical wing took over the LSDSP. As a result, Fēlikss Cielēns left the Central Committee to become Latvia's ambassador to France in 1933 – Menders accused him of "careerism," and the extremist victory of Menders, Buševics and Lorencs is seen as indicative of the crisis in Latvian democracy by Cielēns. (Vol. II of Laikmetu maiņa. Lidingö: Memento, 1963).

There are several different phases in Rainis' thinking; there's the period of the New Current, for example (Rainis' importation of German Marxist literature was a watershed moment in Latvian history; "The Trunk with the Dangerous Contents," Ģērmanis calls it in his Piedzīvojumi [it was actually two trunks, and some Latvian intellectuals had already been exposed to Marxist literature in the so-called Pīpkalonija group at Tartu]) -- the Dienas Lapa period, when he worked and argued with Pēteris Stučka, who later led the bloodthirsty Iskolat Republic and laid the foundation for Soviet law. In 1905, Rainis criticized the terror. Rainis' sister Dora married Stučka, and she wrote from Moscow in 1918 (when Rainis was still in exile in Castagnola) to offer him a place in the Socialist Academy in Moscow. His delayed response sets forth his views on the dictatorship of the proletariat (and compromises his democratic principles, in Priedītis' view).

See Rainis' "Atklāta vēstule Jaunajam Vārdam: Par tautības un kosmopolītisma jautājumu (Atskats uz kādu neizdevušos sabiedrisku mēģinājumu)" ("An open letter to Jaunais Vārds: Concerning the national question and cosmopolitanism [A failed social experiment in retrospect]") -- in Kalnā kāpējs, vol. XVI of Raksti. Västerås: Ziemeļblāzma, 1965).

It's in this text -- written in 1917 and consisting primarily of reflections on the work of the Latvian exiles in Switzerland, justifying his withdrawal from the Comité d'études en faveur des Lettons -- and in his notes and letters from the period that we can get a clear view of Rainis' beliefs. For example, in a letter to Austra Krauze dated 21 January 1916. (a writer who ran the Latvian propaganda bureaux in Switzerland and Berlin from 1916-20, Austra Krauze-Ozoliņa later founded the magazine Ho-Ho in Rīga; in exile in Paris during the Ulmanis régime, Krauze-Ozoliņa was a Red agente provocateuse but also a double agent, working for both the Communists and the Fascists, apparently deriving some perverse pleasure from her activities [she confessed to Aspazija] -- she tried to get Cielēns involved in various plots, and convinced him to travel with her to Valencia in an attempt to liberate Colonel Ozols, who'd been falsely imprisoned by the Republicans as a Fascist agent while fighting in the International Brigades... Cielēns overheard her saying "Und wenn er schuldig ist, dann muss man ihn erschießen" -- when Cielēns and Krauze returned to Latvia, after the Soviet invasion, it was Krauze who denounced Cielēns to the Russians [though she had been denounced as "dubious" by the Communist Party newspaper Cīņa in the 1930s]; she and her lesbian lover committed suicide in a hotel in Rome in June 1941).

Rainis to Krauze: "We will gain autonomy and the Latvian nation will survive despite those who leave it and its detritus. And the only policy that will achieve this is that of an autonomous nation with democracy and socialism."

From another letter to Krauze, 22 June 1916: "We must get rid of the idea that we can only survive at the mercies of the Germans or Russians. The proletariat and social democracy also require a nation, and a free nation. The proletariat suffers the most from the repression of the nation. The proletariat and social democracy can only achieve its goals through the International, but this is based on nationality -- on the existence of the nation. (To kill a nation of a couple of a million is the same as killing a couple of million members of the proletariat.) Cosmopolitanism is a utopia and old-fashioned. A nation-less situation is only a distant goal, but not a means toward that goal. The cosmopolitan is a rabble, a disorganized mass in which nations are held captive. The cosmopolitan is sawdust and chaff, not grain or wood to be worked with."

Rainis to Fēlikss Cielēns, 8 October 1916, regarding the Lithuanian-Latvian conference: "He ["T." -- Traubergs? -- trans.] ought to know that the Latvian nation is a democratic nation; that the nationalities question is a question for the nation and so a question for social democracy. If we want -- or, more precisely, if I want (since I'm the only person wanting, so far) to join with the Lithuanians to work together for national autonomy together, then I want this as a social democrat, standing on the foundation of social democracy, i.e. the foundation of the nation; not as a cosmopolitan fantasist but as an international realist. T. and you don't want Latvians to be mixed with the dark Lithuanians to arrive at an average literacy rate of 52%. Neither do I. But both our nations are one, by blood. Even a poor and foolish brother is still a brother. And a joint Latvian-Lithuanian nation would truly be incomparably stronger than us alone. Do you also want to push away half a million Latgalians, because they're uneducated? If we only count the educated, how many will there be? A couple of thousand. We'll educate the Lithuanians! I want a great politics, a whole nation, not a handful of intellectuals whose works evaporate in speeches. Here I must compliment your beloved wife: her instinct in favor of the Lithuanians has determined a better course than that mind of yours that I hold in such high regard. Our comrades the social democrats have forgotten how to think with their hearts, but where the heart doesn't help thinking, the mind alone becomes minuscule, and all its thoughts and determinations are merely trivial. So our official party has descended to bureaucracy and betrayal, but we want a great politics: to make the Latvian nation greater, to gather our brothers; we want to liberate both branches of our nation, and then to join in the great struggle for the freedom of all nations."

From the open letter to Jaunais Vārds, published in 1917: "The current phase of development calls for the organization of nations in national units -- not the self-destruction of nations -- to attain full development. These national units would join together in larger and larger units, until they would cover continents and humanity itself, and perhaps new, larger nations with new languages would emerge, perhaps with a shared language and other individual languages. This would not be mechanical cosmopolitanism but the work of organic entities and union among these entities."

From a letter to Mednis, 21 January 1926: "In some quarters there are complaints about the Jews' strivings for autonomy -- cultural autonomy with the goal of cultivating a people and bringing it closer to the collective life of the state must only be welcomed, since it strengthens the state. I am familiar with the convivial cultural life of freely developed nationalities from my time in Switzerland, and I know how strongly every French, German and Italian feels Swiss. I want to point out another example: the Warsaw Jew is in every way a committed Pole. And who shall say that Heine isn't German? And have our own Jews not given us such a notable man as the late Sigfrīds [sic] Meierovics? [...] The organism of the nation must be healthy so that all of the nationalities can be brought into harmony, and then diversity makes the life of the state more multi-faceted and full."

My crude translations; his italics throughout. The context of part of his Swiss exile (including some material on the relations between the Latvians and Lithuanians) is given in Alfred Erich Senn's The Russian Revolution in Switzerland (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1971).

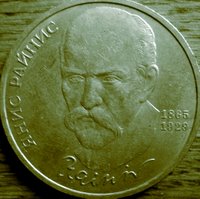

The photograph is of a Soviet ruble minted in 1990; the Soviets lionized Rainis, skipping over and censoring his nationalism, just as the right has often disregarded his socialism.